Cameroon

Rethinking Solutions to Protracted Child Soldiery Problem

Abstract

Child soldiery remains a persistent and devastating issue in many parts of the world, with profound consequences for the children involved and the broader society. This article aims to critically examine the causes underlying the continued prevalence of child soldiers, the impacts on childhood development, and the international efforts undertaken to combat this problem. The analysis will explore the complex socioeconomic, political, and cultural factors that contribute to the recruitment and use of children in armed conflicts, including poverty, lack of educational and economic opportunities. It will then assess the severe physical, psychological, and social impacts that child soldiery has on the healthy development and wellbeing of these young individuals. Finally, the paper will provide a comprehensive overview of the international legal frameworks implemented to address child soldiery. It will recommend strategies to more effectively prevent the recruitment of children and facilitate the sustainable rehabilitation and reintegration of former child soldiers. The findings of this study are intended to inform policymakers, humanitarian organizations, and local communities in developing holistic, rights-based approaches to end the use of children in armed conflicts worldwide.

Introduction

The practice of child soldiery remains a global challenge. Hundreds of thousands of children around the world have been recruited and used by armed forces and armed groups in a variety of roles, from support functions to direct participation in hostilities. Girls and boys have been forced to serve as fighters, cooks, porters, spies, and even for sexual purposes (UNICEF, 2007). While there is no universally accepted description of child soldiers, the Paris Principles generally describe a child soldier as “any person below 18 years of age who is or has been recruited or used by an armed force or armed group in any capacity, including but not limited to children, boys and girls used as fighters, cooks, porters, spies or for sexual purposes.” (Oyewole, 2018, ICRC, 2013, UNICEF, 2022). This definition by the Paris Principles is generally accepted. Children can become involved in armed conflicts in direct combat roles, but also in supporting roles being forced or coerced to become cooks, cleaners, porters, intelligence gatherers and spies, wives, sex slaves, or used in acts of terror. Regardless of their role, the experience for girls and boys is devastating (World vision, 2021).

Local source

According to the United Nations International Children’s Emergency, fund, UNICEF (2022), over 105,000 verified cases of children were recruitment as soldiers between 2005 and 2022, though the actual numbers are believed to be much higher. Africa, home to the world’s youngest population, has been particularly hard-hit, with an estimated 118 million children residing within 50 kilometers of an active conflict zone in 2020 (Faulkner, 2024). Countries in the Sahel region, as well as Nigeria, Sudan, South Sudan, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Somalia have all grappled with persistent child soldier recruitment over the past decade. (Faulkner, 2024).

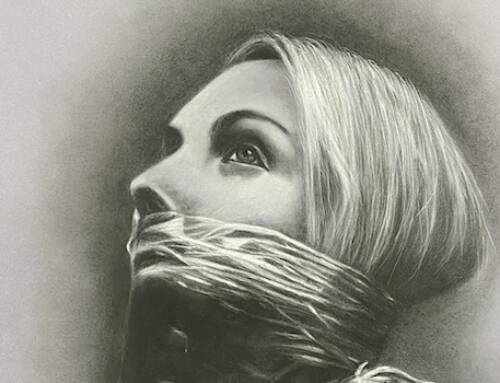

Amidst the distressing reality of child soldier recruitment, it is crucial to illuminate the grave circumstances arising from the ongoing armed conflict in the English-speaking regions of Cameroon even though undocumented. In 2021, the conflict took a disturbing turn as separatist fighters actively engaged in sharing a multitude of images, including the one presented here, across various social media platforms. These images served as powerful tools for the separatist fighters, illustrating a disconcerting surge in the number of individuals rallying behind their cause and a troubling escalation in the recruitment of new members.

The armed conflict in the English-speaking regions of Cameroon has become a matter of immense concern, aggravating the already dire situation of child soldier recruitment and further exacerbating the hardships faced by children residing in the region. The consequences of this conflict have been deeply unsettling, casting a long and dark shadow over the lives of innocent children who find themselves ensnared in the vicious cycle of violence and forced into roles as child soldiers.

The international community has made efforts to remedy the practice of child soldiery but despite the international efforts to stop this practice, children in conflict zones still face the serious threat of recruitment by state and non-state actors. There is therefore need to rethink strategies on how to combat this situation. This article seeks to understand why children join armed groups, the devastating impacts on their development, and the international efforts to combat this practice. By examining the root causes, consequences, and responses to child soldiery, the article aims to suggest more effective strategies to protect vulnerable children in conflict zones around the world.

Why Children Join the Fight

At the heart of the child soldier crisis there is a troubling question what drives young, impressionable minds to take up arms and join the ranks of armed groups? The answers are as complex as they are disturbing. Children join the armed forces for a number of reasons. In some cases, their actions are completely voluntarily, in other instances they act out of desperation, whilst other children become victims of participation because they are forced or abducted into the army (Singh, 2007, Faulkner, 2024)

Children often join the army after their homes had been decimated by fighting in the area and their family scattered and/or killed in the fighting. In such circumstances, for these children left alone, the ‘army’ provided a refuge where the recruits were assured of shelter, food and protection. These children are drawn into the fighting force which becomes a ‘safe haven’ and surrogate home for them. (Singh, 2007). For youth with few other options, the armed forces can seem like the best, or even the only, path to survival and security.

Seeking Security: In some instances, children voluntarily join armed groups out of a desire to defend their communities from violence and oppression (UNICEF, 2022). This dynamic speaks to the complex realities faced by children living in conflict zones. When formal systems of governance and security fail, they may perceive armed groups as the only viable option for preserving their community’s well-being, even if it means taking up arms themselves. This need for security and protection is a particularly powerful draw for some child recruits. When their homes and communities have been devastated by conflict, the armed group may represent the closest thing to a “safe haven” these children have left.

Financial Enticements by Armed Groups: Armed groups are all too aware of this vulnerability and will actively exploit it, using monetary incentives to lure children into their ranks. (Brownell, and Praetorius, 2015, Singh, 2007, Faulkner, 2024, UNICEF, 2022). In many conflict-affected regions, children and their families face dire economic realities marked by poverty, lack of opportunity, and limited access to basic resources. Faced with such disparate prospects, the prospect of generating income through military service can become a powerful draw. Children may see joining an armed group as a pathway to securing a steady paycheck, resources like food and clothing, and even the potential to support their loved ones. This financial incentive can be especially compelling when there are few other viable options for earning a livelihood. There are also examples of children who joined the various armed forces because of the financial incentive provided. For instance, in the case of children being recruited for the fighting in Cote d’Ivoire, children interviewed by Human Rights Watch indicated that they were lured with offers of cash between $300 and $400 if they were prepared to take up arms. Others indicated that, in addition to the money for their own services, they were given ‘money, rice and clothing to encourage their friends to join’. In many of these cases, the initial contact was made by someone known to and trusted by the children. (Singh, 2007)

Coercion; Some children are abducted, threatened, coerced or manipulated by armed actors. (UNICEF, 2022). Most children are recruited because they are seen as valuable resources. Militant groups may use children as “human bombs” because they attract less suspicion. They take advantage of children’s susceptibility to manipulation and loyalty because of their limited cognitive development and desire for social (UNICEF, 2022; Faulkner, 2024). Coercion, manipulation, and outright abduction are all too common tactics, as ruthless commanders view youngsters as ideal recruits, less likely to question orders and more expendable on the battlefield. These children find themselves trapped in a living nightmare, both victims and instruments of the very violence they were meant to escape.

Lack of Education Fuels Child Soldiery. Child recruitment is a byproduct of adverse societal conditions, such as limited education and employment opportunities. For many children living in conflict-affected regions, the path to becoming a child soldier is paved by a lack of access to quality education and meaningful economic prospects (Brownell, and Praetorius, 2015). When children are denied the chance to learn, grow, and build a viable future for themselves, they become prime targets for recruitment by militant groups. Without the stabilizing influences of school, family, and community, these vulnerable youth find themselves idling, lacking the resources and support systems that could otherwise steer them away from the battlefield. Rebel commanders capitalize on this desperation, offering them “work”. Moreover, the disruption of schooling during times of violence and unrest further exacerbates the problem. For example, at the begging of the Anglophone crisis, schools were shot down completely and during the conflict, school infrastructures were destroyed and displaces populations, children were left with few alternatives beyond joining armed groups. This vicious cycle traps successive generations in a spiral of poverty, Violence, and militarization.

Seeking Revenge: For some children, the decision to join an armed group is rooted in a desire for vengeance. They may have witnessed the killing or displacement of family members at the hands of rival factions, which fostered a deep-seated anger and thirst for retribution. (Singh, 2007 This passion for revenge can become a powerful motivator, as children come to see the armed group as a vehicle for exacting justice and restoring a sense of personal or communal honor). Most at times, children lack trust in the government. (Singh, 2007) and believe the government are incapable of standing for and protecting them. This motive at times is not necessarily born of direct, personal loss. Rather, it can stem from a broader sense of injustice and distrust in the government’s ability or willingness to protect their community. When formal systems of justice and security are perceived as failing, children may gravitate towards armed groups that present themselves as champions of the people’s struggle. (Singh, 2007)

However, certain children are more vulnerable to underage recruitment, whether voluntary or forced. A majority of child soldiers in almost every conflict are taken from the poorest, least educated, and disenfranchised communities. The contributing factors include: living in poor areas of the conflict zone; living in the conflict zones without families being a member of particular ethnic, racial, or religious group; and associating with armed groups for protection. Child soldiers are often recruited through abduction from homes, schools, and streets or through forceful induction following the killings of family members. In addition to increasing the number of soldiers, warlords recruit and use child soldiers for unique reasons including, they are: easily manipulated; easily used in battles; adventurous; able to quickly learn fighting skills; cost less; pose a moral challenge for enemies; and pose no competition for leadership roles.

Impacts on Childhood Development

As compared with adult counterparts, Child soldiers are more likely to experience higher casualty rates due to their limited experience, knowledge, and maturity level. (Brownell, and Praetorius, 2015). The impact on child soldiery on a child`s development is multifaceted, including physical danger, psychological trauma, and disruption of their education. (Singh 2007). Stevens, (2013) outlined some of the effects of child soldiery of childhood development, theses will be examined in the following paragraphs.

Children who have been associated with armed groups may face rejection, stigma, and difficulty reintegrating into their families and communities. This can be exacerbated by the psychological distress they experience. Some children who attempt to reintegrate are viewed with suspicion or outright rejected, while others may struggle to fit in. Psychological distress can make it difficult for children to process and verbalize their experiences, especially when they fear stigma or how people will react. What’s more, families and communities may be coping with their own challenges and trauma from conflict, and have trouble understanding or accepting children who return home.

Child soldiers often suffer from serious physical health issues due to their involvement in armed conflicts. They may have untreated bullet wounds, bullets stuck in their joints or brain, joint damage, loss of limbs, loss of sight, and loss of hearing from being near artillery fire. Some children are used in suicide missions because they are less likely to be searched and may not fully understand the consequences of their actions. In some cases, child soldiers are given drugs and alcohol to prepare them for battle. This can lead to drug addiction and withdrawal when they escape or leave the armed groups, which can make it harder for them to recover. Before battles, young soldiers are sometimes given drugs like amphetamines and tranquilizers to make them feel brave and less sensitive to pain. These substances can have serious negative effects on their physical and mental health.

The collapse of community infrastructures during conflict limits availability of nutritious food, during wars, it’s hard for people to get good food, clean water, and medical care. This means that many child soldiers get sick and some even die because they don’t have enough to eat or because they get sick from dirty water. Girls who are soldiers often live in bad places with lots of other soldiers, which makes them more likely to get sick. Sometimes, the people fighting in the war don’t give enough food and medicine to child soldiers, so they get sicker than other soldiers. They might also use drugs or alcohol, which hurt their bodies and minds.

Many former child soldiers have PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), often caused by witnessing or taking part in violent acts like executions, attacks, or seeing dead bodies. These traumatic experiences can lead to problems like anxiety, nightmares, depression, and suicidal thoughts. Girl soldiers often have more severe PTSD than girls who were never part of armed groups. Exposure to war and violence during their formative years can permanently damage a child’s personality and how they see the world. Some child soldiers were forced to do extremely brutal acts, like cutting people’s throats and eating their body parts. This can make them less able to feel empathy or trust others. Girl soldiers are often sexually abused and forced to become “wives” or sex slaves for leaders. This can lead to serious health problems like pelvic infections, infertility, and a high risk of HIV/AIDS. Unwanted pregnancies are common, and unsafe abortions can also cause health issues. It’s very difficult for former child soldiers, especially girls who might have had a child in the process, to reintegrate into their communities. They may be rejected or labeled as “whores”, making it hard for them to go back to school or find work. Some turn to sex work to support themselves, putting them at risk of more violence and disease.

Severe trauma and stress in childhood can have long-term negative effects on a child’s brain development, learning, and overall health. While some stress can be beneficial, chronic and uncontrollable trauma can severely damage a child’s mental and physical well-being.

International Efforts to Address the Use of Child Soldiers

The recruitment and use of children by armed forces or armed groups is a serious violation of child rights and international humanitarian law (UNICEF, 2022). The international community is aware of the problem of child soldiers. As a result, the use of child soldiers has been explicitly prohibited by various international treaties under international human rights law, humanitarian law, criminal law, and even labor law. This section will examine some of these treaties.

1. The Paris Commitments and Principles and Guidelines

After reviewing the unlawful act of children being constantly recruited and used by armed forces during armed conflict, UNICEF and partners agreed on the need to draft principles to protect children from being recruited into armed forces during conflict. This led to the development of two documents: the Paris Commitments to Protect Children Unlawfully Recruited or Used by Armed Forces or Armed Groups (“The Paris Commitments”) and the Principles and Guidelines on Children Associated with Armed Forces or Armed Groups (“the Paris Principles”), which provide more detailed guidance for implementing programs (UNICEF, 2007). The objective was to prevent the unlawful recruitment of child soldiers and provide guidance on disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) by drawing on lessons learned from global experience. The two documents were formally adopted by 58 States in February 2007.

2. The Additional Protocols to the Four Geneva Conventions of 1949

The Geneva Conventions of 1949 set out detailed rules of international humanitarian law, including the rights and obligations regarding children in armed conflict. The Additional Protocols reflect the rules as relevant to specific situations, namely the protection of victims of international armed conflicts (Additional Protocol I, 1977) and the protection of victims of non-international armed conflicts (Additional Protocol II, 1977). Both Additional Protocols prescribe 15 years as the minimum age for children to be recruited into or used for armed hostilities, at both government and non-government levels.

3. The Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1989

The Convention on the Rights of the Child defines a ‘child’ as someone under the age of 18 years. However, for the specific purpose of engagement in armed conflict, the Convention (article 38) defers to the Geneva Conventions and uses the lower age of 15 years as the minimum for recruitment or engagement in any form of armed hostilities. The Convention urges state parties to take all feasible measures to ensure that persons under 15 years do not take a direct part in hostilities.

4. The Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, 2002

The Optional Protocol takes a positive step by providing expressly for 18 years as the minimum age for a child to be compulsorily recruited into armed groups or for direct participation in armed conflict. However, it still does not prevent armies from accepting children younger than 18 who voluntarily sign up for service, nor does it prohibit children younger than 18 from being used for involvement other than in direct armed conflict situations.

5. The International Labor Organization’s Worst Forms of Child Labor Convention 182, 2000

This Convention includes all persons under the age of 18 years in its definition of a ‘child’ and specifically includes ‘forced or compulsory recruitment of children for use in armed conflict’ as one of the worst forms of child labor. While the Convention prohibits the use of children under 18 in armed conflict, it allows for the voluntary recruitment of children aged 16 and above, subject to certain safeguards.

6. The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, 1998

The Rome Statute is an attempt to regulate the activities of the International Criminal Court and define its scope of operations. Within this framework, the Statute delineates war crimes, covering both state-led actions and non-governmental internal conflicts. Specifically, Article 8(2)(b)(xxvi) declares it a war crime to conscript or enlist children under the age of 15 into national armed forces or use them to actively participate in hostilities. Similarly, Article 8(2)(e)(vii) addresses internal armed conflicts, prohibiting the conscription or enlistment of children under 15 into armed forces or groups, or using them in active combat. While the Statute sets the age threshold at 15, it goes further by explicitly proscribing both direct and indirect involvement of children in hostilities. However, the enforcement of this provision is challenging, as many states lack the necessary domestic legislation to prosecute such offenses as war crimes.

7. The African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, 1999

This is the only regional charter that specifically addresses the issue of child soldiers and children in armed conflict. Adopted by the Organization of African Unity (OAU), the Charter came into force in November 1999. Unlike other instruments, the Charter does not differentiate between those under 18 and those under 15, simply defining a child as anyone below the age of 18. Article 22(2) requires state parties to take all necessary measures to ensure that no child shall directly participate in hostilities and to refrain from recruiting any child. The Charter’s comprehensive approach to the age and nature of hostilities appears to address the shortcomings of other international instruments. However, Africa remains one of the regions with the highest incidence of child soldiers, highlighting the persistent gap between the written protections and the enforcement of these standards by national authorities. This is evident from the continued use of child soldiers, the lack of sanctions against offending parties, and the failure to adequately provide for the reintegration of these children in most peace treaties.

Conclusion

Child soldiery has had a devastating impact on the lives and development of countless young children. The exposure to the horrors of war, ranging from rejection by their communities to severe trauma, malnutrition, torture, and sexual violence, leaves a long-lasting mark on these children’s physical and mental well-being. Despite the existence of various international treaties and frameworks aimed at addressing this issue, the practice of recruiting and using child soldiers persists unabated in many parts of the world. The unfortunate reality is that these well-intentioned legal instruments often remain mere words on paper, with little tangible action or enforcement taking place on the ground. Holding the perpetrators accountable in the midst of active conflict situations has proven to be an immense challenge, further compounding the difficulties in eradicating this practice. It is painfully clear that the international community has yet to find an effective and comprehensive solution to the problem of child soldiery. While efforts have been made, the stark truth is that much more needs to be done to combat this grave violation of children’s rights and ensure that these vulnerable young lives are protected from the horrors of war. Only through a sustained and concerted global effort can we hope to finally break the cycle of child soldiery and restore the fundamental rights and dignity of children who have been robbed of their childhood.

Recommendations

- Addressing Root Causes: addressing child soldiery stars from dealing first with managing conflicts. greater percentages of child soldiery happen in places where there is conflict and to escapes such practices in conflict situation is always unrealistic. So far as conflict persist child soldiery will also persist. Governments should therefore try to promote good governance to prevent and manage conflicts

- Increase focus on prevention: Address the causes that make children vulnerable to recruitment, such as poverty, lack of access to education, and instability. Invest in community-based programs that provide livelihood support, education, and psychosocial services for at-risk children and their families. Engage with armed forces and groups to develop age verification procedures and strict policies prohibiting the recruitment of children.

- Strengthen domestic legislation: Encourage states to enact robust national laws that explicitly criminalize the recruitment and use of children under 18 in armed forces or groups and ensure these laws enable effective prosecution of offenders and provide for appropriate sanctions.

- Enhance enforcement and accountability: Improve monitoring and reporting mechanisms to identify and document instances of child recruitment and use. Establish effective international and regional mechanisms to investigate, prosecute, and punish perpetrators, whether state or non-state actors. Impose targeted sanctions, such as arms embargoes or financial restrictions, on parties that continue to use child soldiers.

- Enhance protection and reintegration: Ensure the demobilization of all child soldiers and their safe release from armed groups. Provide comprehensive rehabilitation and reintegration support, including mental health services, vocational training, and family/community reintegration assistance. Establish effective disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) programs that prioritize the needs of child soldiers. Equipping them with skills and opportunities for education helps rebuild their lives.

- Strengthen international cooperation and coordination: Promote greater collaboration between states, United Nations agencies, and civil society organizations to develop and implement holistic solutions. Leverage regional and international frameworks, such as the Paris Principles and Commitments, to harmonize approaches and share best practices. Increase funding and resource allocation to support programs and initiatives targeting the prevention of child soldiery and the rehabilitation of former child soldiers.

The key is to adopt a holistic approach that combines strengthened legal frameworks, strong enforcement mechanisms, preventive measures, and comprehensive rehabilitation and reintegration programs to effectively address the complex issue of child soldiery.

Reference

- Amy Jane Stevens (2013). The invisible soldiers: understanding how the life experiences of girl child soldiers impacts upon their health and rehabilitation needs.group.bmj.com

- Christopher M. Faulkner (2024). Title:Why Child Soldiering Persists in Africa. Georgetown Journal on International Affairs.

- Divya Singh (2007). When a child is not a child: The scourge of child soldiering in Africa. AFRICAN HUMAN RIGHTS LAW JOURNAL

- Gracie Brownell, and Regina T Praetorius, (2015). Experiences of former child soldiers in Africa: A qualitative interpretive meta-synthesis. International Social Work, Vol. 60(2) 452–469: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0020872815617994 journals.sagepub.com/home/isw

- ICRC, (2013). Children associated with armed forces or armed groups. International Committee of the Red Cross 19, avenue de la Paix 1202 Geneva, Switzerland T +41 22 734 60 01 F +41 22 733 20 57 Email: shop@icrc.org www.icrc.org

- ICRC, (2003). Legal Protection of Children in Armed Conflict

- Neil Boothby, Allan Rosenfield and Bronwyn Nichol (2011). Child Soldiering: Impact on Childhood Development and Learning Capacity. PEIC

- Temitayo C. Oyewole (2018). The Proliferation of Child Soldiers in Africa: Causes, Consequences and Controls. Maastricht University

- UNICEF, (2007). The paris principles; principles and guidelines on children associated with armed forces or armed groups. UNICEF (rsymington@unicef.org)

- UNICEF, (2022). Children recruited by armed forces or armed groups. Thousands of boys and girls are used as soldiers, cooks, spies and more in armed conflicts around the world. Unicef.org

- UN, (2000). Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict. www.un.org

- UN, (1989). Convention on the Rights of the Child

- World vision (2021). Child soldiers: What you need to know. Yuko, a former child soldier. World vision