Nigeria

Egrets in the Sun; How High can Street Children Dream?

Calabar shyly dresses up in fancy thrift clothes. Her coastal visage, flattened by low buildings and lush green streets, echoes the glories of what the city was and what it could become. Her people, like herself, calmly shy away from ambitious expectations, complacent in the thrill of commonness that has over the years become a worthy compromise for peace.

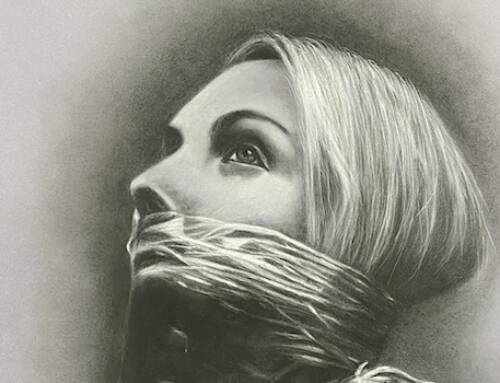

In the heart of the city, the underbelly of not-so-shege poverty is etched into every cracked roadway and early closing all-night bars. At the center of the busiest street stands a mahogany tree, its branches waving to the surrounding markets and bustling traffic. Before sundown, a flock of pristine egrets wing their way from the southern skies, seeking refuge on the mahogany tree. With graceful elegance, they settle in, stretching and preening their snowy feathers. Meanwhile, a group of carefree street children, slanderously known as ‘skolombo’ by the locals, engage in a playful game of tag with the birds. They toss small objects at the egrets, watching as each targeted bird unfurls its radiant whiteness to the sun before fluttering to a neighboring branch. At sunset, tired from their play, they return to what is the most real of their fantasies-survival.

These children exist among the busy markets and teeming streets, their skinny limbs tactically maneuvering cars and pedestrians. Some are outright abandoned, while others have families too impoverished to provide for them. They roam in packs, eking out a meager existence by begging, performing menial labor, or petty crimes like pickpocketing. At night, they take shelter wherever they can – abandoned buildings, market stalls, or directly on the streets. Vulnerable and alone, they face daily threats of violence, sexual exploitation, addiction, and criminality. Dreams of education, healthcare, and a better future are dreams conditioned to remain dreams. But by who? What?

This neglected population represents one of the most complex global human rights crises of our time. The 1989 United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child outlines fundamental protections to which all children are entitled – rights to survival, development, protection, and participation. Yet for Calabar’s street children and millions more around the world, these internationally recognized children’s rights remain shamefully unmet.

Consider the inherent right to survival and life enshrined in Article 6 of the convention. How can this be fulfilled when these children lack access to sufficient nutritious food, clean water, shelter, and basic healthcare? Many are trapped in a vicious cycle of poverty, illness, and an inability to meet their most basic needs. Or look at the right to education under Article 28. Denied schooling, these children are robbed of opportunities to develop talents and skills, acquire knowledge, and break out of the generational poverty that plagues their communities. The rights to play, leisure, and freedom of expression under Articles 31 and 13 are distant dreams undermined by the daily struggles to simply exist.

Perhaps most criminally neglected are the rights to protection from abuse, exploitation, and cruelty under Article 19. The streets expose these vulnerable young lives to unfathomable violations – physical and sexual violence, hard labor, substance abuse, human trafficking, and being forced into criminal activities for survival. Their childhoods are tragically stolen.

Neglect is one of the pure forms of inhumanity. Who then is responsible for upholding the rights of Calabar’s street children? Historically, the buck has been passed from households, to communities, to an overextended government operating in a developing nation with enormous resources sucked in by corrupt leadership. But renewed local and international focus on this crisis is pivotal for change.

Sustainable strategies must be enacted to move beyond temporary handouts and shelters. Comprehensive policies promoting socioeconomic empowerment, preventive family services, educational access, youth employment programs, mental health support, and legal protections are crucial. Community grassroots initiatives, nonprofit partnerships, corporate social responsibility efforts, and mobilization of religious and cultural groups can all play a role.

The upheaval of COVID-19 shed further light on how quickly youths can fall into crisis when existing societal safety nets falter. Now is a critical window for leaders to prioritize this underserved population with proactive, rights-based interventions before another generation is perpetually lost to the streets.

On May 27th, Nigeria commemorates Children’s Day, a joyous occasion marked by vibrant celebrations. In Calabar, schoolchildren gather at designated squares, their crisp uniforms a testament to the occasion’s significance. With proud smiles, they march past, saluting dignitaries who return the gesture, their promises of a brighter future etched on their faces, even if their bulging agbada-clad bellies betray the sincerity of their electoral vows.

Meanwhile, under the mahogany tree, street children await the kindness of jollof rice from strangers, a small comfort on their special day. Above them, egrets perch, their long, slender bills glowing a deep burnt orange under the irate Calabar sun.

Obinna Okwesili