SPEECH BY JOACHIM GAUCK

Speech by former Federal President Joachim Gauck on 50 years of IGFM

Dear Mr Brand,

Dear Professor Shieh,

Dear Mr Lamm,

Dear Mrs Bornmüller,

Ladies and gentlemen,

If this is the second time that I have accepted your invitation to speak at your conference on the occasion of a milestone birthday, then you can already take two messages from this. Firstly: Even after another twenty years, your work is still of great importance. And secondly: My gratitude for your work at the time when I myself still belonged to the oppressed is unbroken. So I would like to take this opportunity once again to thank you – the members of the International Society for Human Rights – for your work and to strengthen your backs for your future challenging tasks. Before I do so, however, I must and would like to address current events.

As we celebrate your 50th Annual Conference together today, almost exactly on the day of its founding on 8 April 1972, we meet in times of war in Europe and our thoughts are with the people in Ukraine, our sympathy is with all those suffering persecution, hardship and war.

Since 24 February 2022, Russia has been waging a murderous war of aggression against a peaceful, democratic state on the border with the European Union. For over six weeks now, Ukrainian cities have been bombed, and in some cases razed to the ground. From day one, Putin’s terror has been indiscriminately directed against women and children, soldiers and civilians, who are killed, wounded, displaced and abducted. And if there was still a last spark of hope that this war between the “brother nations” would not result in terrible crimes again, then this spark has finally been extinguished since last weekend, when the pictures from Butchah and many other places in the north of Kiev reached us. Once again we freeze before the sight of executed women and men, corpse next to corpse on the roadside, whole families wiped out and buried.

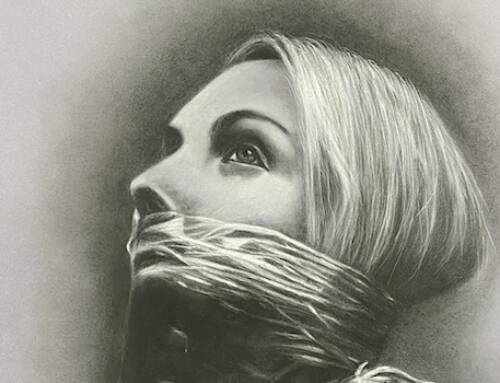

Former Federal President Joachim Gauck gives the keynote speech on the occasion of 50 years of IGFM on April 9, 2022.

Once again we look at crimes in bewilderment and are confronted with the question: What does “never again” demand of us in this situation? Don’t these ruthless acts of murder constitute a humanitarian intervention to protect the people of Ukraine? We know that even those who do not act can be guilty. But we also know that in this case we are faced not only with a major moral dilemma, but also with a geopolitical one. With its nuclear arsenal, the Russian aggressor also poses a direct threat to ourselves. And so there are understandable reasons for us to shy away from becoming an active party to the war ourselves. The realisation that our options are limited and that there are also legitimate interests to be safeguarded does not absolve us of responsibility, nor does it make the moral dilemma any smaller. On the contrary: we are called upon to do everything to the limit of what is possible for us to put an end to Putin’s murderous activities.

For from day one, the role in this conflict was very clearly divided between perpetrator and victim. There cannot and must not be moral and legal equidistance from the parties to the conflict. In view of this situation, the German government has rightly initiated a U-turn in security policy, wants to stand by Ukraine to help repel Russia’s aggression – also with weapons. And many people in Germany are showing their solidarity, they are helping and supporting, they are donating, they are setting signs, they are sympathising, and not a few are despairing that it is so difficult to oppose Putin even more decisively and substantially. That is why it is so important that we – and by that I mean the citizen as much as the politician – keep asking ourselves the questions: Are we providing enough support to the courageous Ukrainians? What more can we do to stand by them? Is it responsible to continue importing gas and oil from Russia? How do we stand before those who lose their lives if we continue to pay murderers?

We also feel that it is not just a distant country that is to be attacked and subjugated. We feel that we are included if Ukraine is to be deprived of its self-determination. Putin’s war is ultimately aimed at the free world, at liberal democracy. True to his Leninist character, he sees power once won as something that must never be surrendered. Thus he continues – albeit without communist ideology – what he once advocated, now justified in nationalist and neo-imperialist terms: Human and civil rights do not apply, neither does the rule of law, the separation of powers is non-existent, public space is devoid of freedom of expression and assembly – a dominated society. No one knows how far Putin’s ambitions go in re-establishing a Greater Russian Empire. No one can say that incursions into Poland or the Baltic states are out of the question in the future.

Almost everyone was mistaken – or should I say wanted to be mistaken – when they believed that stability and peace had finally taken precedence over imperial power-seeking. The older ones among you still remember the tank socialism of the Soviet Union and the suppression of freedom aspirations in the streets of Berlin, Prague and Budapest. These memories have become distant memories in recent decades. Instead, we have given in to the belief that economic interdependence would automatically lead to liberalisation and rapprochement with Putin’s Russia. In retrospect, this picture seems to be an embellished reality.

I have not yet mentioned the Soviet-era practices carried out by the dictator at home. Denounced as a “foreign agent”, “Memorial” was banned, an institution that rendered great services in coming to terms with Stalinist crimes, an organisation that restored dignity to millions of victims of the Soviet dictatorship and enabled their relatives to honour their memory. The Russian opposition activist Andrei Nawalny, who was awarded the Sakharov Prize by the European Parliament last year for his courage in the fight for freedom, democracy and human rights, is also to be silenced. The regime, which first tried to murder him in cowardice, has locked him away in a prison camp, where he is serving arbitrary sentences.

Illusions about Russia’s intentions and our possibilities to influence them through economic interdependence – especially in the area of energy policy – did not exist in Ukraine, nor among our eastern neighbours and the Baltic states. Much more clearly than we in Germany, these countries are familiar with Russian influence and interference in their democracy. In vain, they have alerted us to the dangers that have long been visible here as well – just think of the hacker attack on the German Bundestag or Russian propaganda and disinformation campaigns aimed at undermining trust in state institutions and sowing discord among the population. Already 8 years ago, the Russian campaign against Ukraine began with the Crimean annexation and the support of the separatists in the Donbas.

Welcoming of former Federal President Joachim Gauck by IGFM Honorary Chair Katrin Bornmüller (2nd from right), Chairman Edgar Lamm and Board Member Carmen Jondral-Schuler

Ladies and Gentlemen,

The terrible images of war before our eyes make it clear that your commitment, your self-given mission and not least the theme of your conference “Human Rights Outreach More Important Than Ever” are of the utmost urgency. For 50 years now, as a non-profit, non-governmental organisation, you have been standing up for people who are working for the realisation of human rights in their countries or who are persecuted for demanding their rights. Founded by former political persecutees and committed people, the basis of your work is the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights. You campaign for worldwide respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, including freedom of the press and freedom of expression, freedom of conscience and religion, freedom of assembly and association.

And you stood up for political prisoners in the GDR – unlike many others who were blind in one eye. In the years of the Cold War up to reunification, the IGFM successfully stood up for thousands of politically persecuted citizens of the GDR. I would like to expressly acknowledge this today and express my sincere thanks.

As a former Commissioner for State Security Documents, I also know only too well about the work of the Ministry for State Security vis-à-vis society, a destructive, corrosive work that was partly perpetrated by willing helpers in the West of the Federal Republic for money or out of political-ideological conviction. The Ministry for State Security had more than 100 informers working on the infiltration of West German human rights organisations. Of these, 30 were assigned to the IGFM alone. And as late as 1989, unofficial collaborators were sent from the GDR to the West. And yet they were not deterred and helped, clarified and denounced.

At the same time, the files show that the commitment to human rights is worthwhile. They show how much a totalitarian regime like the GDR felt attacked by the publication of the conditions in the prisons. These files also show that the GDR leadership was extremely embarrassed when the state-imposed discrimination against those willing to leave the country became known.

The enforcement of human rights is a permanent task! Human rights are universal and indivisible – and so is the responsibility for them. Human rights are innate and inalienable – they apply to everyone. They are based on the incontrovertible fact that we human beings are equal simply because we are human, despite any cultural, religious, social or other differences that may exist. Those who strengthen human rights therefore strengthen humanity as a whole.

Former Federal President Joachim Gauck in conversation with Prof. Dr. Obiora Ike, member of the IGFM Board of Trustees, Director of the Globethics Foundation, Geneva, and former Vicar General of the Diocese of Enugu, Nigeria.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

I was eight years old when the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted by the United Nations. And I was 11 years old when I experienced state repression in the GDR. My father was abducted for no reason at all by the Soviet secret police in 1951 and sentenced, along with other innocent people, to 25 years of forced labour in Siberia in a secret trial. I learned what it means when a loved one disappears from the family and – after years of uncertainty – finally returns, badly scarred in body and soul. My family was lucky. For thousands and thousands throughout Central Eastern Europe did not survive the communist system of injustice. Anyone who has ever felt such powerlessness never wants to allow it to happen again, not in their own family and nowhere else. The most successful advocate for human rights is within us – it is a deep inner knowledge of the dignity and rights of every human being. But obviously it sometimes takes the most atrocious transgressions to give this knowledge political validity. The idea of human rights is centuries old and has been enshrined in the American and French constitutions for over 200 years. But it was not until the great break in civilisation of the Second World War with mass murder and the Holocaust that the international alliance was brought together in 1948 to agree on a common catalogue of human rights.

After the Second World War, the world community needed a new intellectual-political, but also moral foundation. It had become indispensable to protect the individual and his or her inalienable rights – regardless of ethnicity, religion, skin colour or gender.

Although the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was initially “only” a declaration of intent, not a binding law, it was one of the greatest promises formulated in living memory. And it did not take long for it to become national law in many states. Equality and freedom, civil, political, economic, cultural and social rights: the foundation was laid in 1948 for so much of what we find today in great differentiation.

For me, the history of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is therefore also a history of man’s political willpower. We have experienced it again and again in Central and Eastern Europe in the past century: it was human rights and, after 1975, also the Helsinki Final Act, to which the courageous could refer when they defended themselves against their oppressors, against violence and arbitrariness.

Former Federal President Joachim Gauck with IGFM activists

But if we look back over the last decades and take stock of the development and spread of human rights, the results are sobering. Too often, human rights – are only a promise for the future. We have to call them that because many millions of men, women and children all over the world do not yet experience these rights as a reality, but as a great unfulfilled longing. In numerous states on almost all continents, human rights have been and are being ignored, relativised and subordinated to the interests of rulers, clan chiefs, warlords or party leaders. Reports from many parts of the world show how people are driven out of the country because they belong to the supposedly “wrong” ethnicity, religion or party, or because they are persecuted for their political views, their sexual orientation and do not want to give up their freedom of expression.

Never before has the number of people who can no longer live where they are at home been as high as it is today. More than one percent of the world’s population was on the run in 2021 – over 84 million people. In Europe, too, we see the terrible consequences of war, conflict and persecution: Already, over four million Ukrainians have embarked on an arduous flight, leaving their homeland indefinitely. And people have been fleeing across the Mediterranean to Europe for years. And often they find death.

At the same time, it is now 74 years since representatives of all continents adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights at the United Nations and proclaimed rights for all people for the first time. Worldwide. Without distinction and regardless of national or social origin, ethnicity, skin colour, gender, language, religion, political or other opinion, wealth, birth or other status.

Together we must ask ourselves: Why have individual states, why has the international community in the last seven decades, despite all declarations of intent, often not been able to prevent orgies of violence, genocides, serious human rights violations? Why are many countries able to close their borders entirely to refugees?

The reasons may be complex. It may be ignorance, cold-bloodedness, or even excessive demands in terms of realpolitik – all of these are evident in many areas of conflict around the globe, sometimes even at the negotiating table. We are also familiar with the disregard and marginalisation of human rights when it comes to enforcing economic interests. In a globalised economy with multiple dependencies – be it on resources or goods – we cannot disregard our economic interests. But we can also no longer indulge in naïve notions and must recognise that the Chinese leadership is also not only concerned with peaceful trade, but with global supremacy.

Former Federal President Joachim Gauck between Prof. Dr. Shieh, Jhy-Wey, the representative of Taiwan in the Federal Republic of Germany, and Michael Brand MdB, spokesman of the CDU/CSU parliamentary group in the Committee on Human Rights and Humanitarian Aid of the German Bundestag (left).

We must react all the more clearly when, from this direction, human rights are relativised with reference to cultural differences or even discredited as “Western imperialism”. Those who claim this are mistaken and deny that the Declaration was a compromise of 52 states of different cultural and religious backgrounds. Among the 48 states that agreed to the Declaration, almost all continents, or “regional groups” as the United Nations would say today, were represented.

Those who deny the universalism of human rights deny that the roots of human rights lie in the most diverse cultures of our earth. They fail to recognise that they are our most important global asset. And he is blind to the fact that the oppressed in every country of the world understand the language of human rights very well. Everywhere, human rights are the hope and longing of countless people; they encourage the powerless to resist and to fight for a self-determined life in freedom.

This also applies to another issue that you regularly raise but is too rarely noticed by the public: The threatened or denied freedom of religion. This issue affects almost all societies and religions. That is why it always amazes me how little is known about the persecution of Christians around the world. Worldwide, 340 million Christians are considered to be subjected to high to extreme levels of persecution. And the number of Christians killed has actually risen sharply in recent years. They are largely due to persecution by Islamist groups in Africa. Incidentally, this is a topic that is not given enough attention in our media.

Former German President Joachim Gauck with Olga Karatch (left), founder of the Belarusian human rights organization Nash Dom, and Jurgita Samoskiene, chairwoman of the IGFM section Lithuania.

We can and must draw attention to the fact that members of religious minorities in Muslim countries are subject to severe repression. We can be confident of this much differentiation if, at the same time, we do not close our eyes to the fact that members of the Muslim faith in particular are persecuted in other countries. And we do not close our eyes to the fact that hatred and aggression against members of minority religions are growing in Western democratic countries. Three out of four people live in a country that restricts their freedom of religion or belief. Violations of human rights are often also violations of religious freedom in the everyday political life of many countries.

The extent to which human rights can be implemented also depends on attentive accompaniment, advice and the tenacity of civil society: without the courageous people in NGOs, the implementation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights would not be where it is today. They remain indispensable as a source of impetus and corrective. On today’s anniversary of the IGFM, I encourage you: do your work tirelessly. I thank you for helping to ensure that we do not turn a blind and deaf ear, but that we sensitise ourselves to wrestle again and again for the highest good we have: human dignity. For we are all “endowed with reason and conscience and should treat one another in a spirit of brotherhood”. So says Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Our world needs people who not only know these words, but are moved by them. We have experienced it: injustice can be defeated, freedom and justice are possible. We want to believe in this and fight for it together.

Without the courageous people in NGOs, the implementation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights would not be where it is today. They remain indispensable as a source of impetus and a corrective. On today’s anniversary of the IGFM, I encourage you: Do your work tirelessly. I thank you for helping to ensure that we do not turn a blind and deaf ear, but that we sensitise ourselves to wrestle again and again for the highest good we have: human dignity.

Joachim Gauck, 2022