Uganda

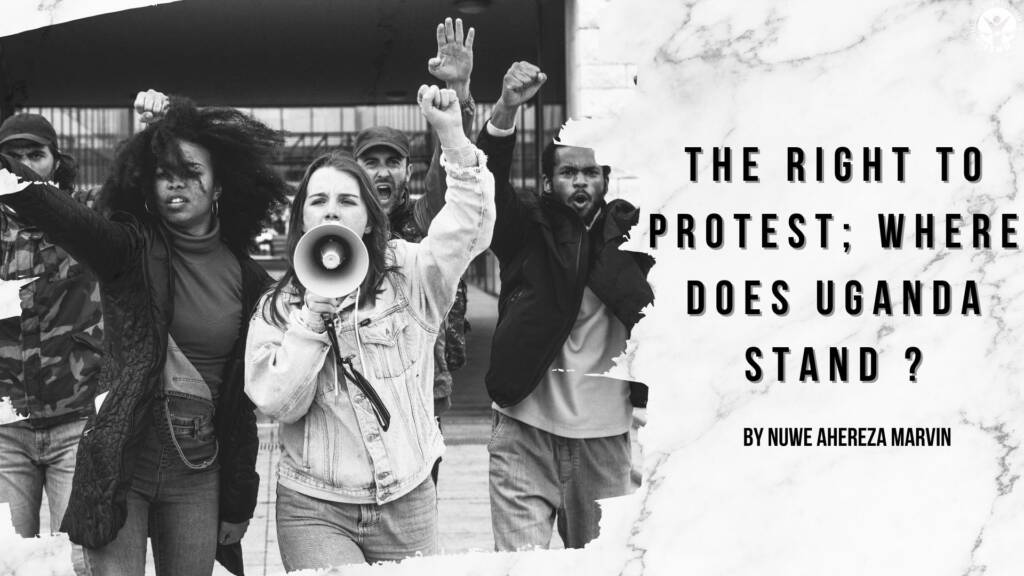

The Right to Protest: Where Does Uganda stand?

About a month ago, I wrote an article on social media activism and whether its retreat activism. My main arguments were that social media activism in countries like Uganda can’t be a standalone form of activism and must be used in form of hybrid activism along with physical activism in order to achieve the best achievable results. The most recent example of this form of activism is reflected in the Kenya protests. For context, the protests were youth driven by the Gen Z calling for the rejection of the controversial Finance Bill, 2024. These protests took Kenya by storm while also influencing and sparking prospective protests in other countries in Africa. In all this, Kenya’s neighbours especially Ugandans had cause to reflect on what rights they exactly have and what do they actually do to repel poor governance and human rights violations in their own country.

Uganda’s isn’t exactly well off! It suffers from poor governance, corruption and unceasing human rights violations which are evidenced in its poor human rights record. As recent as 2020 in the wake of the Covid 19 pandemic, many Ugandans have taken to social media to show their discontent with how the country was being governed and to condemn and call out poor governance and many human rights violations suffered on them. This mobilisation was and is still being mainly done on social media platforms such as X, Facebook and WhatsApp and most recently through exhibitions of poor governance and human rights violations.

However, Ugandans have been reluctant to take to physical protests and this isn’t because they aren’t aggrieved enough and pushed to the corner. It is because the price to pay for these types of protests is fatal often culminating in the worst forms of human rights violations in the form of severe injury, arbitrary arrests, abductions, torture and cruel and degrading punishments and in some cases extra judicial killings. This isn’t new in the world of protest as the civil rights activist Malcolm X once stated that, “The Price of Freedom is Death.” However, should it be this way!

Many civil society organisations and activists have adopted the term, the right to protest. The right to protest isn’t expressly provided for in the international bill of rights and neither does it expressly exist in the constitution of Uganda but it is read from the amalgamation of the right to the freedoms of conscience, expression, movement, assembly and association provided for in article 29.

However, these freedoms even in the most tolerant countries have limitations mainly premised on public order. In Uganda these limitations can be justified under article 43 of the constitution. The state might permit the right to protest ordinarily for protests with no probability of success however the state will seek to enforce these limits when the protests become more likely to succeed. Thus, when the masses take to the streets, they have to contend with the overwhelming with the public order apparatus ready to but them down. These public order limitations have been tested in the courts of Uganda in cases such as Muwaga Kivumbi v Attorney General and Human Rights Network and 4 ors v Attorney General where the court struck down provisions in the police act and the public order management act respectively that in effect limited the right to protest and in violation of constitutionally guaranteed rights to freedoms of assembly, expression, movement and association.

The right to protest is a crucial pillar for a working democracy. It enables the populace to raise awareness about the issues affecting them and create pressure for change through solidarity and unity while galvanising their collective efforts to seek accountability from the government. The right to protest is a testament of a working democratic government and the lack of it or its violation is a reflection of the institutional weakness of the government. It should thus be protected and guaranteed not only as a human right but also a guarantee from the social contract concluded between the state and its people evident in Uganda’s constitutional order under article 1 of the constitution that affirms that,

“All power belongs to te people who shall evercise their soverignity in accordance with this constitution.”

Nuwe Ahereza Marvin